He aha te mea nui o te ao? What is the most important thing in the world? He tangata, he tangata, he tangata. It is the people, it is the people, it is the people. (Maori proverb)

He aha te mea nui o te ao? What is the most important thing in the world? He tangata, he tangata, he tangata. It is the people, it is the people, it is the people. (Maori proverb)

By Roger Childs

Whatever people’s ethnicity, Waitangi Day is for all New Zealanders. In 2020, it marks the 180th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, sometimes called “our founding document”.

This agreement guaranteed certain rights to all people living in the country at the time, both Maori and European, in exchange for British sovereignty.

Sadly in recent years, the formalities at Waitangi have sometimes been marred by protests, political grandstanding and the jostling of dignitaries.

Hopefully, 6 February 2020 will be a time when we celebrate unity in diversity, and media reports will be able to focus on people getting together in positive ways [but you can guarantee any hostility will get all the attention — Eds] and enjoying the national holiday. This is what happens in Australia and Canada on their national days.

Bicultural to multicultural

In 1840 New Zealand was a thinly populated country with peoples from two cultures:

- descendants of Polynesian and other Pacific migrants who began arriving a few centuries before

- settlers of European origin, mainly from Britain, Western Europe, New South Wales and the United States.

Today we are a cosmopolitan society with citizens from almost every cultural and national group on the planet.

So the biculturalism of 180 years ago has given way to a rich tapestry of ethnic influences in the 21st century.

Whatever their origins and when they arrived, all the people of New Zealand are equally important, and Waitangi Day should celebrate our diversity and the cultural variety in our communities, as well as the many things we have in common as Kiwis.

A beautiful day

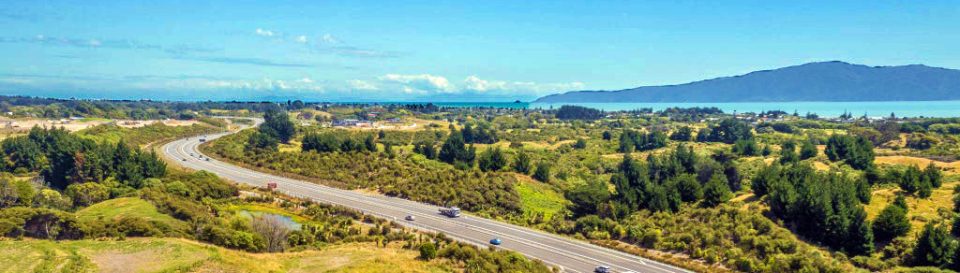

Hopefully there will be good weather around the country and, in Kapiti, people will no doubt enjoy themselves.

- In Waikanae getting out on the beach, in the sea and along the river trails.

- Down in Wharearoa Farm people wandering around the tracks and mountain bikers heading up and down the hill trails.

- In Paekakariki the cafes doing a roaring trade with locals and visitors, cyclists who have come through Queen Elizabeth Park and trekkers off the challenging Te Araroa Trail from Pukerua Bay.

- People using the redeveloped Mclean Park and patronising the many cafes and fast food outlets.

- Adults and children having tram rides, riding on horses and visiting the Marine Memorial and the replica hut in Queen Elizabeth Park.

- Families enjoying themselves at Whareroa Beach – swimming, picnicking and having barbeques.

- Plenty of excited kids using the Splash Pad in Marine Gardens at Raumati. (I first saw one on these in South Korea 23 years ago and should have taken-up the New Zealand franchise!) There is also the miniature railway, the beach close by and interesting walks in the area.

No doubt elsewhere around the country the local population and visitors will be doing similar things and having a pleasant and relaxing summer’s day.

That’s what our national day is (or should be) all about: not political debate, jostling visitors and arguing over who has rights to what. Rather, enjoying the holiday and having quality time with family and friends.

Before the Treaty — New Zealand in the 1830s

Maori and Europeans engaged with each other when either side saw some benefit in doing so. Trade, conversion to Christianity, education, literacy and personal relationships of all degrees were the actual frontiers where these encounters and exchanges took place. —Historian Paul Moon

No British desire to take over

There was no inevitability about the Treaty of Waitangi until 1839. For the historian the greatest enemy is hindsight and using the knowledge of subsequent events to conclude that it was obvious what was going to happen.

There was no inevitability about the Treaty of Waitangi until 1839. For the historian the greatest enemy is hindsight and using the knowledge of subsequent events to conclude that it was obvious what was going to happen.

In the decade before 1840 there were plenty of things happening in a “country” that was inhabited by scores of scattered tribal communities of Pacific Island origin. There were perhaps 80,000 natives plus a small, but growing minority of about 2,000 European settlers, mainly British.

Up until 1838 the British government had no inclination to intervene in New Zealand and set up another expensive colony. It was well aware that “European” settlement was increasing, but was reluctant to interfere, and remained content to let the Governor of New South Wales monitor the evolving cultural interaction across the Tasman.

Varying degrees of interaction

The scattered native tribes (variously called indigenous people, Aborigines, savages, natives, New Zealanders, but not Maori), had been rapidly killing each other off since the 1800s in the devastating Musket Wars. In over 500 battles tens of thousands of indigenous people had been killed or wounded by 1840, and thousands more innocent men, women and children had been slaughtered and often eaten, or taken as slaves. Furthermore, unfamiliar diseases were affecting the population.

European influences on the native peoples increased as the decade wore on, but the degree of interaction varied enormously. The tribal groups of the north had the greatest contact, with white missionaries, traders, settlers, seamen, escaped convicts and travellers. It was also here that Britain had appointed a Resident named James Busby.

No concept of a nation

New Zealand in the 1830s had no government or political structure either indigenous or British. As mentioned above, the native tribes were regularly at war with one another and there was no concept of a united Polynesian nation.

Busby in 1835 did concoct a Declaration of Independence, mainly to head off the threat of Frenchman Baron De Thierry laying claim to New Zealand. But this attempt to impose nationhood was only signed by a small minority of 35 chiefs, mainly from Northland, and it never established a political system.

Nevertheless, the British government did accept the declaration, but with reservations. Colonial Secretary, Lord Normanby, stated in his instructions to William Hobson in 1839 we acknowledge New Zealand as a sovereign and independent state, so far at least as it is possible to make that acknowledgement in favour of a people composed of numerous, dispersed and petty tribes who possess few political relations to each other…

In theory the Governor of New South Wales kept an eye on the growing impact of Europeans in the country on behalf of the British Colonial Office. Crimes committed in New Zealand could be tried in Sydney, but this rarely happened.

Essentially, New Zealand before 1840 had no laws, judicial system or enforcement authorities. Inevitably there was “lawlessness” in some areas, especially in the north, and this was a major concern for the missionaries, and the powerless Busby who had no means to maintain order.

Applying pressure on the British government

As the 1830s wore on, some British interests, notably missionaries, tried to encourage the government in London to extend its authority over New Zealand. Some wanted protection for the increasing number of permanent white settlers while accepting native rights to their land and customs. Other sought complete annexation and incorporation of the country into the British Empire. Also some Northland chiefs were keen to see the British bring order to New Zealand.

As the 1830s wore on, some British interests, notably missionaries, tried to encourage the government in London to extend its authority over New Zealand. Some wanted protection for the increasing number of permanent white settlers while accepting native rights to their land and customs. Other sought complete annexation and incorporation of the country into the British Empire. Also some Northland chiefs were keen to see the British bring order to New Zealand.

However, the British government was extremely reluctant to commit to taking over “the country”. It would be expensive establishing a colonial government, with a judiciary and defence force to support it.

Nevertheless the European influence in the country was rapidly increasing: there were more Protestant mission stations opening up and the French Catholics joined the Christian mix in 1838.

Furthermore, trade across the Tasman, farming, forestry, whaling and the flax industry were expanding and some of the native population took advantage of these economic opportunities. All these activities, plus increased land purchases by settlers and speculators, lead to a growing white population, mainly British.

The British decide to act

Plans late in the 1830s by the New Zealand Company to buy large areas of land and formally settle areas of central New Zealand, lead to major discussions in the Houses of Commons and Lords on the future of the country. Who would govern any new British settlements and what effect would they have on the indigenous people?

There were significant concerns about law and order and the lack of authority over the Europeans in New Zealand, and successive New South Wales governors expressed their dissatisfaction with the ineffective Busby. Consequently in May 1839 he was dismissed. Now without any British representation in New Zealand the government in London needed to act.

In the end, it was probably the concerns over the likely status of the New Zealand Company’s planned settlements in Wellington, Wanganui and Nelson that galvanized the Colonial Office into action. There was a ship full of Wakefield settlers on the high seas in late 1839 and the British government was concerned, amongst other things, about the legality of the land purchases the Company agents were making.

There had been requests made by native chiefs to the British monarch from 1831 for guardianship and protection. However these were largely initiated by missionaries and it is debatable whether these tribal leaders would have been willing to cede sovereignty to Britain and accept a consequent loss of mana.

Lord Normanby instructs…

In August 1839 the Acting Colonial Secretary gave detailed instructions to Captain William Hobson about reaching a settlement with the native tribes of New Zealand. Normanby did not tell the new Consul to annex all of New Zealand and made it clear that any agreement must be with the free and intelligent consent of the natives.

Britain wanted to protect the natives and emigrants (future British settlers) from the evils of a lawless state of society. So the main object of Hobson’s mission was to adopt the most effective means for establishing a settled form of civil government. But only over the areas of New Zealand that they (the Aborigines) may be willing to place under her Majesty’s dominion.

Hobson was exhorted to act with mildness, justice and perfect sincerity. How he handled his crucial mission in early February 1840 has become the basis for a great deal of debate, to put it mildly.

Waitangi: Sovereignty, Property And Rights

He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people. —Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson to each chief after he had signed the Treaty of Waitangi

What it meant at the time

It was 6 February 1840 and the location was an elevated area above the Bay of Islands known as Waitangi. The British government’s envoy, Captain William Hobson, had called tribal and settler leaders together to sign a treaty.

In examining the significance of this agreement, people need to understand what the signatories understood at the time.

This was a treaty about the scattered native peoples of New Zealand, through their tribal leaders, ceding sovereignty to the British government in exchange for

~ having the ownership of their lands, dwellings and property (taonga) protected

~ becoming British citizens.

There was no Waitangi Tribunal, no new 1980s back-translation into Te Reo Maori, no mention of partnership or principles.

Passing sovereignty over to the British government

So was the sovereignty of New Zealand placed in the hands of the most powerful nation on the planet? Absolutely.

There was no way the British were going to agree to joint governorship deals with what Lord Normanby, who gave Hobson his instructions, called … numerous dispersed and petty tribes who possess few political relations to each other..

Henry Williams, and his son Edward, were experts in the Maori written language which they had helped devise. For “sovereignty”, they chose the Maori term for governor – kawanatanga – and added tanga to make the word ‘governorship’.

Henry Williams, and his son Edward, were experts in the Maori written language which they had helped devise. For “sovereignty”, they chose the Maori term for governor – kawanatanga – and added tanga to make the word ‘governorship’.

Many of the tribal leaders who signed had a working knowledge of English, but regardless, from what the chiefs said at Waitangi, especially those who would not sign, they were obviously clear as to what the treaty meant.

Ceding sovereignty to the British Crown was the basis of Article the First.

Guaranteeing ownership of property

This guarantee of ownership was the key point in Article the Second. It was extended to land and dwellings, and the Crown was given the “exclusive right” to purchase land that the tribes wished to sell. The guarantee also extended to the European settlers.

How about property? There has been great debate over the use of the word taonga in the Maori translation of the Treaty, as today is means “treasures” which cover a wide range of elements.

The critical point is not what “taonga” means today, but what it meant the signatories in 1840.

- Property acquired by the spear. Hongi Hika’s definition of taonga

- .. nothing but timber, flax, pork and potatoes. Nga Puhi chiefs understanding of taonga

In 1840 it did not mean “treasures” and everything that word conjures up. It meant property as defined in Thomas Kendall’s and Samuel Lees’ Maori dictionary and grammar of the time.

Maori become British citizens

In Article the Third, the people of New Zealand (everyone: Polynesian and European) gained the rights and privileges of British citizens. This was in exchange for the cession of Sovreignty to the Queen.

Such rights were not given to the natives in South Africa or Australia until the second half of the 20th century, even though those peoples had lived in their “countries” for thousands of years.

An 1840 treaty

There have been various versions of the Treaty of Waitangi in circulation, with the latest being a back translation into Maori by Professor Hugh Kawharu in the late 1980s. He translated taonga wrongly as meaning “treasures”, which is was not what it meant in 1840.

He also included other subtle reinterpretations of the original treaty draft. He had vested interests – for a time, he was on the Waitangi Tribunal and was also a claimant.

The Tribunal has made a meal of the new meaning of taonga, leading to hundreds of millions of dollars of claims and payouts to the part-Maori descendant of tribes up and down the country.

For all New Zealanders, regardless of their ethnicity and mixed ancestry, the Treaty

- is the country’s founding document

- ceded sovereignty to the British Crown

- guaranteed the ownership of their property to all New Zealanders

- extended citizenship rights to all.

As Hobson reiterated at the time: We are now one nation.

Waitangi Day is a symbol of grievances on both sides and if anything the country is becoming increasingly divided. Most people will take the holiday and try to forget what it’s for.