By Tony Orman

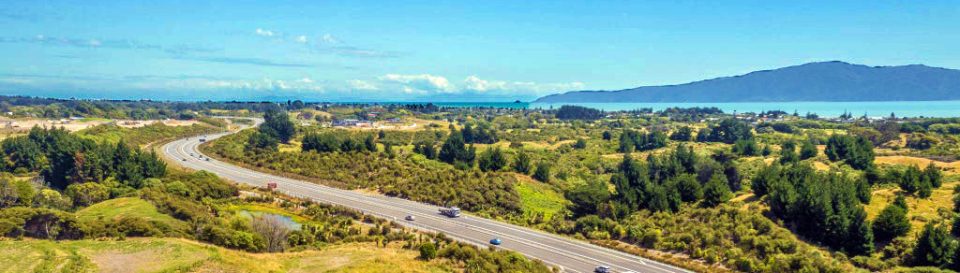

Climbing up form Otaki Forks

Somewhere about 1958 John Henderson and I went hunting in the Tararua Ranges behind Otaki. We had slogged from the Otaki Forks up to Field Hut and then further up onto the snow grass tops to Kime Hut.

Field and Kime Huts had been built in the Depression years by the Tararua legend Joe Gibbs and helpers. Timber was pit sawn on site. Some thirty years later Kime Hut atop the main range and constantly exposed to the full blast of the ferocious northwesters and cold southerly gales was starting to sag. A couple of floor boards were missing and a sole possum living under the hut made nocturnal forays into the sleeping/living area.

Out on a clear morning

John and I were holed up by a cold, sleety southerly storm for two days. But on the third day it was a clear, crisp morning so we went hunting.

We sat and spotted several deer but saw nothing we desired to kill. So with cameras we stalked a hind and five month old “fawn” some 200 metres below us, getting to just twelve metres from the pair. Suddenly the deer spotted us. Quickly I rose and the Agfa 120 mm camera’s shutter clicked loudly. Then the deer were gone.

The Agfa 120 was an old bellows camera with no telephoto.

On the black and white negative the deer image was disappointingly small and it needed a friend to enlarge the photo. The grain-speckled image gave it a lack of quality. But still, even now when I look at the photo, I get a feeling of deep satisfaction.

Hunting with the camera

Then came 35 mm cameras with telephoto lenses producing “colour slide” transparencies or film. Using black and white film, in the Marlborough high country I got within ten metres of a young six point stag and photographed him. It was a great feeling. Today that framed photo reminds me of a great hunting morning.

But digital cameras were the big breakthrough in term of photographing wild deer. Probably 10 or so years ago, I used a Panasonic Lumix with a 12x zoom on it. It was okay up to a point but things got better. A fishing friend who is a very skilled professional photographer recommended the Canon Power Shot 50 which he used for work as a backup – testimony to its quality.

A 50 times zoom normally is not much good unless you have a tripod but the Canon 50 camera’s stabilisation system greatly smooths out long shots. I really focused on wild game photography such as deer and when the chance arose, wild goats and wild pig. I made mistakes. For example on digital cameras like my Canon, there’s two zooms – the 50 optical zoom then a further extension using the digital zoom of 4x.

Early on with the Canon 50 camera, I encountered two young stags. I zoomed right going through the optical zoom and even closer with the digital zoom. I was full of hope of some stunning shots of the young stags.

When I projected them onto the computer I was very disappointed. There was a loss of quality and the shots were disappointing. The same with a roaring stag, with mouth wide open, bellowing its challenge to other stags. So I sought advice.

“Turn off the digital zoom,” my professional photographer friend told me. “Stick to optical. Digital zoom results in loss of definition.”

Great with a labrador

I’ve always hunted with a dog, a labrador. Labradors are inevitably great companions, good natured and always optimistic and eager for a walk in the hills. Previously I’ve had four labs — all great companions and adept hunters. The fifth is four year old Bing.

The dog is a great advantage in hunting with rifle or the camera, but particularly the latter alerting you to game just ahead. Thus you slow right down to pussy-footing mode, with camera at the ready.

Just the other week, in the hush of the day’s twilight and with the rifle at home, I left the 4WD and slowly walked into the breeze or air drift. Bing was “at heel” beside me. We had covered about a hundred metres along the track flanked by matagouri and manuka interspersed with grassy clearings when Bing indicated a deer was just ahead. The dog had winded (scented) the smell of deer on the gentle breeze. Bing was full of eagerness so I whispered “heel.”

I eased back the pace and in measured steps, camera ready, together we moved forward. It was a yearling red deer but it spotted us first. In the next instant the animal dashed into cover.

I was annoyed with myself. So I slowed our pace down even further.

Just another 50 metres and Bing winded again. This time I was ready and took three “hand held” photos of a young stag with long velvet prongs. Then we encountered a lone deer – a young stag with wee velvet knobs – feeding. Then a hind and fawn. She stared at us then headed uphill and into cover but not before I took three shots of her.

I spooked another deer which I didn’t get a shot at. But that was compensated for when ten minutes later I encountered a South Island bush robin. Sometimes robins just disappear, other times they’re filled with curiosity that brings them in real close.

It had been a great evening with three deer and a robin shot — with the camera. This one was inquisitive.

The camera – a great alternative to the rifle

If you’ve got venison stored in your deep freeze, why needlessly kill a deer? The alternative to the rifle is the camera. It gets you out and that’s the best therapy one can have in an increasingly irrational, at times idiotic and increasingly ugly world. It’s great physically and for peace of mind.

And the deer photos can become trophies of a sort, framed and hung up on the wall in your den or study.

(Tony Orman based in Marlborough is a recreational fisherman and hunter and author of several fishing and deerstalking books.)

A good shot with the camera is as satisfying as a good shot with the rifle.

Hunters need to selectively kill a deer. For example some advocate rather thoughtlessly to shoot hinds to reduce numbers. Firstly where are there too many deer? For millions of years moas browsed the vegetation heavily. What did it look like?

Fairly open I would imagine. The giant Haast eagle needed open forest to fly through.

Still if it’s decided to cull hinds, hinds should not be shot from November to August as in December and into autumn they are raising a fawn. The young deer needs Mum through the winter otherwise it might die or at the best will be a poor, under nourished animal in the Spring.So probably September – October is the time to cull hinds.

You can still go hunting and photograph hinds, November to August inclusive.